What France’s electoral geography looks like

The result of each candidate for the leadership of a particular country is made up of the residents’ preferences of its regions, cities, and even municipalities. At the same time, regional peculiarities can vary greatly, and if left-wing progressive ideas are popular in big cities, the provinces tend to be very conservative. However, this pattern is not only characteristic of every country in Europe, but is probably typical of almost the whole world. There are also more localized phenomena, where in Germany right-wing ideas are common in the former GDR, and left-wing and liberal ideas in the FRG of the 1945-1989 era. In Poland, there is a similar geographical electoral pattern in the lands of the former Russian and German Empire, respectively. In Belgium, Flanders is more conservative, while Wallonia tends towards left-wing ideas. Approximately the same pattern was observed for a long time between the North and South of Italy, until they were united by the far-right party “Brothers of Italy”. In Spain, regions such as Catalonia and the Basque Country were more prone to leftist ideas, while “central” Spain favored moderate liberal-conservatives. However, these are only superficial and the most visible trends, and to examine the regional aspect of the elections in more detail, we will look at France, which is close to us, where various protests have recently been raging, both socially and ethnically motivated, both of which have a strong political component. We will then look at the preferences of French people living in different parts of the country, using the example of the country’s major presidential elections, which took place in April and May 2022.

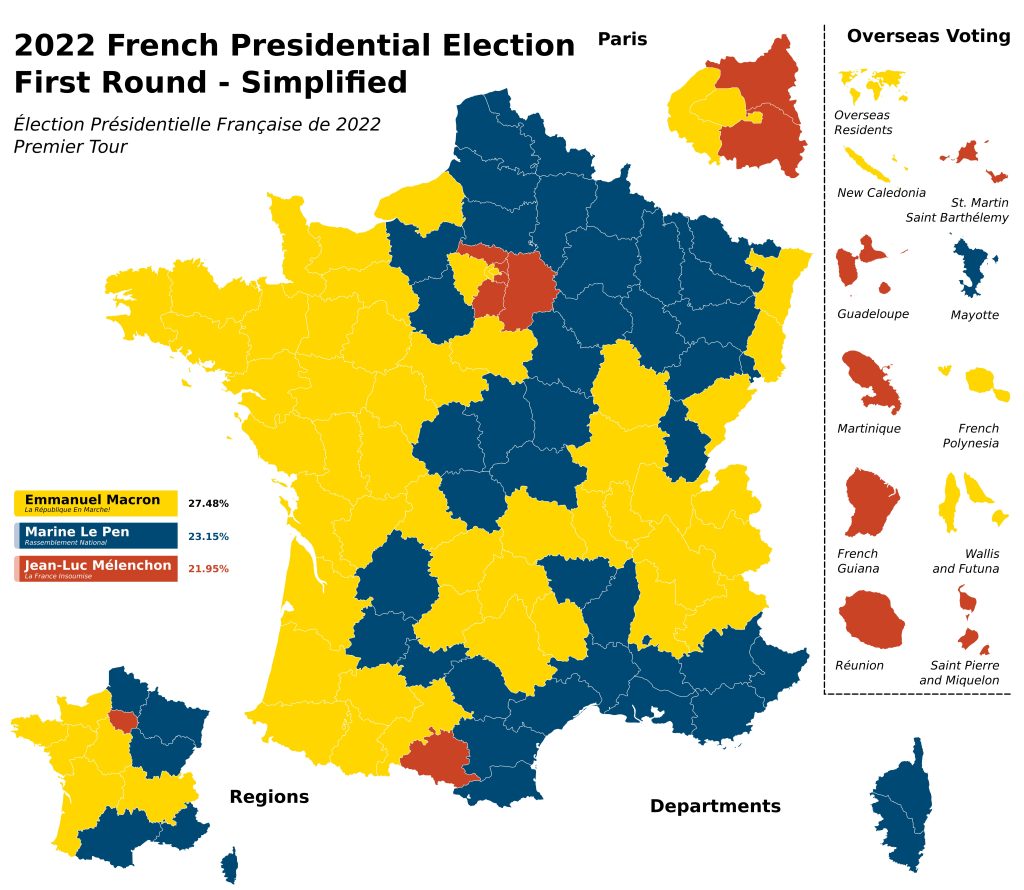

As part of the analysis of electoral geography in France, for each major political current (left-wing in the person of Mélenchon, right-wing in the person of Le Pen and centrist in the person of Macron) we defined “territories of priority”, where their reserves of votes are the largest. We will look at the results of the first round and largely ignore the second round, where voters often chose between Le Pen and Macron not on the basis of their clear policy preferences, but rather on a “lesser of evils” basis, making their motivations a very specific and separate topic. Also, we will pay a lot of attention to the second places in each region, which are often as much a reflection of the political picture as the first. The regional divisions have become much more complex in recent times, because the traditional division between right and left, which drew a binary electoral geography, with each of the two main political forces dominating in certain regions, broke down with the rise of the Macronists in the person of their party “Forward, Republic”, which today has become “Renaissance”. Three major political currents currently share the political and geographical “chessboard” of France, and for each of them the priority territories seem relatively well identified, as can be seen in the map we have put in the title image before the beginning of our article. It shows the winners for each department in the first round of the French presidential election in 2022, where yellow is Emmanuel Macron, blue is Marine Le Pen, and red is Jean Luc Mélenchon. When it comes to the main regions and their departments, it is Paris for the left, Hauts-de-France and the Côte d’Azur for the right, and the Loire, New Aquitaine and Occitanie for the centrists. When examined in detail, however, the picture is much more motley and ambiguous.

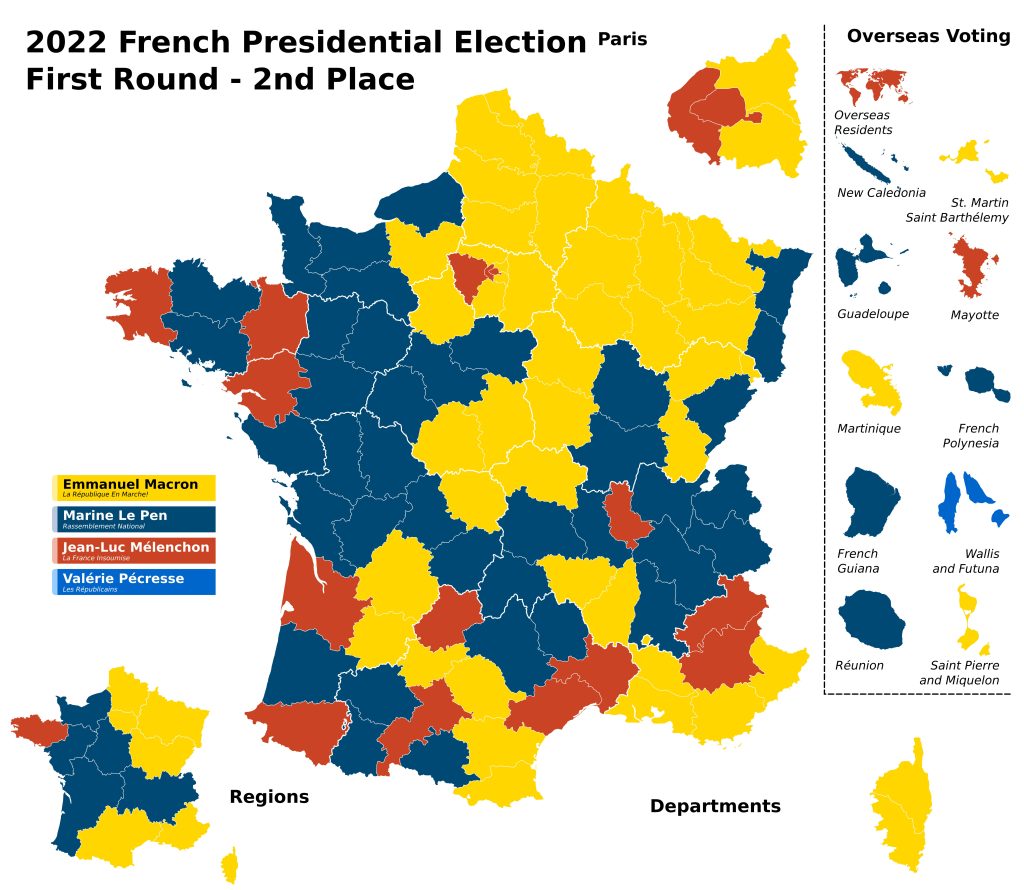

These details are well illustrated by comparing the winner for each department and region with the runner-up candidate, where often the gap is not so clear and obvious, as can be seen in the map below. For example, the seemingly Macron-loyal Brittany is in fact heavily split between nationalists and leftists, making it one of the most oppositional regions in the country. This has both social and ethnic corridors, because the Breton people, although they have largely forgotten their language, retain a part of their national identity, which in itself makes them go against the general line of Paris. It is worth mentioning that a Breton by birth was Vincent Bolloré, who stood behind two candidates at once in the 2022 campaign, Eric Zemmour and Valérie Pécresse. The situation is similar in the Loire Land, which, although formally a different region, is part of historical Brittany with its political and cultural attitudes. In Grand-Est and Hauts-de-France, Le Pen’s positions are popular, as these regions suffer the most from the flow of migrants, many of whom choose them on their way to the UK, and ethnic minorities like Germans and Flemings in these regions are inclined to the right-wing agenda. Macron’s position is also strong there, having taken the same anti-migration tack, but in a more moderate and liberal way that appeals to more conservative voters. Such a model was apparently ideally implemented in Normandy, where the Macronists outperformed the right-wing under the leadership of Edouard Philippe, the popular mayor of Le Havre and the country’s former prime minister, and, in part, in the Centre-Val de Loire. Burgundy – Franche-Comté and Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, looking like a bastion of liberals, centrists and macronists, are actually very right-wing in their rural parts, but very left-wing in big cities like Lyon. The influence of the left and right is also noticeable in the macronist New Aquitaine and Occitanie, and it is significant that Louis Aliot, the husband and closest associate of Marine Le Pen, is an Occitan. For Le Pen herself, in this sense, the nationalist Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Corsica, which massively supported her in the first round, were deceptive. This was due to the fatigue of conservative small towns and villages in these cities with the flow of migrants, which was multiplied by the cultural separatism of Italians in Nice and Corsicans in Ajaccio. However, in larger cities such as Marseille and Toulon, the mood is often quite different and is essentially split between radical leftists and liberal centrists, which is not surprising given the strength of the Arab and African communities in these places. Ile-de-France and Paris, which in the public mind is a bastion of leftist students and migrants, is actually divided between them and a moderate middle class that continues to trust Macron.

The electoral geography of France’s overseas regions and departments is also very interesting. There are also stereotypes here that due to the racial composition of the population, the left should dominate almost totally here, but the reality is that Macron and even Le Pen were popular here. The prosperous and partly “white” Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin and Saint Pierre and Miquelon unexpectedly supported not the right, but the left, and the second place went to the Macronists. In this sense, the victory of the left in Réunion, Guadeloupe, Guiana and Martinique was expected, but the fact that the second place in the last three provinces was won by nationalist Le Pen was a surprise that broke stereotypes. This was because its agenda had recently become much more social, and especially in demand in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean regions, where unemployment is among the highest. In this sense, racial issues have taken a back seat to people who have prioritized their jobs and social stability. Le Pen’s promotion of the “new program” was most successful in Arab and Islamic Mayotte, where she generally won in the first and second rounds. In this sense, Polynesian regions, such as New Caledonia and French Polynesia, proved to be more prosperous and therefore conservative, and they expectedly supported Macron, while Le Pen won second place everywhere.

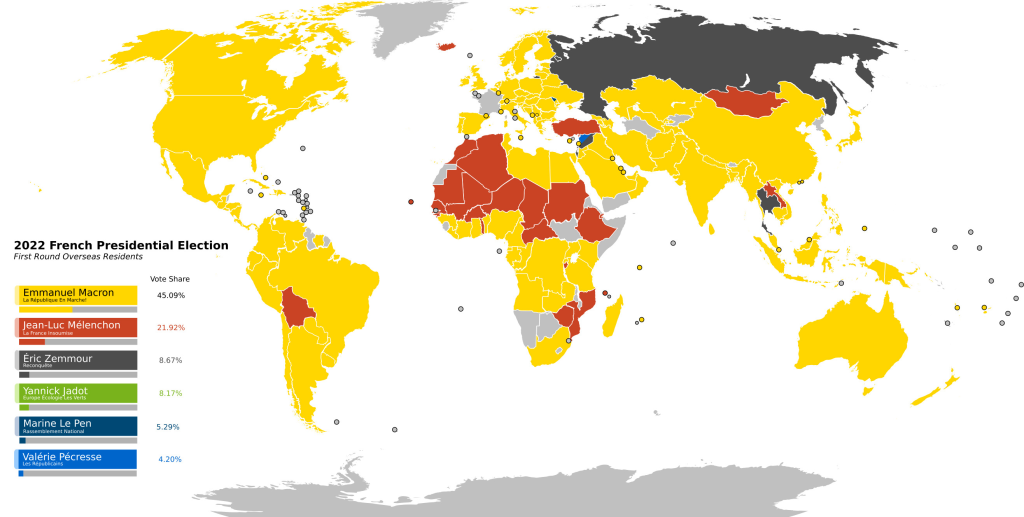

The world geography of voting by French people who lived outside the country was also interesting. With few exceptions, Macron won there. First, this was due to the globalist mindset of the French, who preferred to live outside their homeland and therefore sympathized with the “progressive” Macron, who embodied their liberal views of the world. On the other hand, there was the mobilization of administrative resources through the state embassies, which consolidated the voters in each country, giving primacy to their main boss, who was the president. The coordination of this difficult task was taken on by the then Minister of Overseas Territories, Sébastien Lecornu, who later received for his efforts the honorary post of French Minister of Defense. Nevertheless, there were regions where Macron did not succeed. Tellingly, the left-wing Mélenchon won in almost all Françafrique countries, both reflecting and foreshadowing Macron’s current and future problems in countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Gabon. There were some very unusual exceptions that had at least a formal “Russian footprint,” with Marine Le Pen winning in Syria and Eric Zemmour winning in Russia with only about 7% of the vote in the metropolis. Against this background, in parallel with the development of the contours of electoral geography, the number of people ignoring elections has increased dramatically across the country since 2014. The phenomenon particularly affected the west of the country, in particular the regions of Brittany and the Loire Land, as well as Corsica. At the same time, the turnout in Ile-de-France seemed almost stable, but this was due to the traditionally very low turnout in this region, which has not changed. And this is a very serious process of growing distrust not only in the ruling party but also in all the other parties, which are increasingly seen by voters as different sides of the same coin. In the end, regardless of regions and departments, this can lead to the inflation of democracy and the crisis of the whole system, when people will want to solve their political issues not by elections, but by very different actions, often involving revolutions and violence.

Average Rating