Inflation in Germany: a shock for a population not used to crises

Since the end of World War II, only two parties have ruled in Germany: the CDU and the SPD, which have “rotated” in power only five times. Of course, each of these rotations had social and economic reasons, but most of them did not take place against the background of major crises or deep political disappointment. In 1969, Willy Brandt replaced Kurt Kiesinger, rather because the latter had once worked as an ordinary propagandist in the office of Joseph Goebbels. In 1982, Helmut Schmidt gave up the post to Helmut Kohl because of the public weariness of the “socialist experiment”, in 1998 Kohl, who during this time managed to unite the country, was replaced by Gerhard Schröder, brighter and more flamboyant in the public eye, who embodied the “new” and promising socialism. The Germans got tired of this model rather quickly and in 2005 the post of the chancellor was taken by the conservative and reliable Angela Merkel for 16 years. During all this time, the economic growth remained unchanged, which at first was rapid and then stable, the level of employment remained high and the inflation low.

For the average German, this became almost a constant and did not depend on the change of parties at the head of the country. In 2021 when Merkel was replaced by Olaf Scholz, this was probably the first time that this happened against the background of a rather high level of public anxiety after the migration crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there was hope that this was only a temporary and not a systemic crisis. Alas, the future has shown that it was not.

Apparently, stable growth with constant prosperity in Germany is becoming something of the past, which threatens to hit hard the German mentality, which has established for almost 70 years with a confidence and belief in a bright future. According to the results of September, inflation in Germany amounted to a record 10% in annual terms and there is every reason to believe that before the New Year its steady pace will not reduce. Energy made the main contribution to the increase in prices (+44%). Food prices went up by 18.7% and non-food products by 17.2%. Services, meanwhile, went up relatively by 3.6%, but given the regular problems of small and medium-sized businesses, the situation could deteriorate at any time. According to most experts, price growth indicators are observed in Germany not for the first month and occur against the backdrop of the energy crisis and military actions in Ukraine, along with sanctions measures, complicating the situation in the energy and food markets. Nevertheless, we have to be frank and be aware of what is happening: the underlying reason is not the Ukrainian war and not even the consequences of restrictive measures against the background of the COVID-19 epidemic, but the systemic imbalance that has developed in the economy over the past 10 years, if not more. It will not be solved by cosmetic or even small tactical measures since this situation could remain for many years.

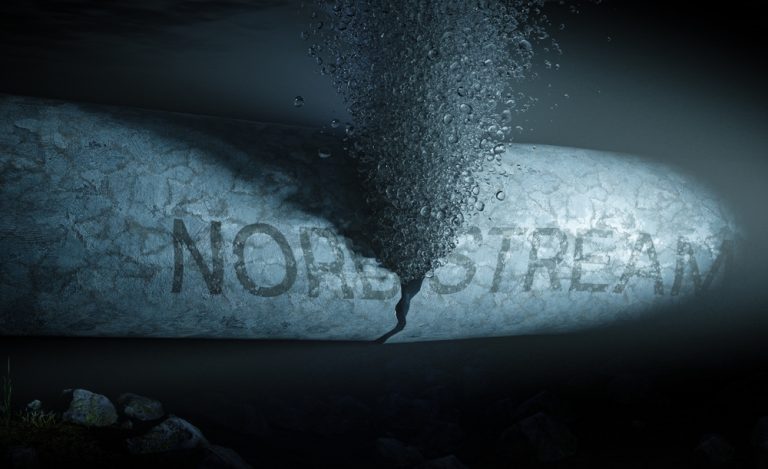

For the sake of fairness, it is also worth noting that the current difficulties regarding inflation are not being dealt with very effectively. The country has been looking for a replacement for Russian gas with varying success, and failures have been eloquent. The only thing the German government has achieved so far is that it has traded its dependence on Russian supplies for dependence on supplies from North America or Norway and all this at the expense of its consumers and industry. The cost of Russian gas was €14 per MWh. The Germans will pay around €50-60 for the same amount of gas if they find alternatives. After that we can safely expect a jump in prices for all goods and services in comparable values. Attempts to curb the price by directive and “regulatory” methods have so far turned only into a farce. A plan to limit gas prices in two stages was developed: in December 2022 and in March-April 2023. However, given the shortage of gas, it threatens to increase prices for other energy sources. Now, according to preliminary calculations, heating with fuel oil, which is used by 10.4 million apartments in Germany, will cost € 3.400 per year. Electricity prices are also rising rapidly. EnBW AG, one of the largest power producers in Germany, is raising the price of basic power supply for domestic consumers in the country by 38% at once, explaining this by the fact that the purchase price has increased fivefold. This augmentation came just a few months after the last large-scale price increase, when tariffs rose by 35 % and by December 1, prices will rise by an average of 38%.

It was the energy crisis that was the first marker of the gloom and depression into which formerly confident and optimistic Germans were sinking. According to Bloomberg, in Berlin the crisis creates disturbing echoes of the post-World War II desolation, when a fuel shortage caused residents to cut down almost all the trees of the central Tiergarten Park for heating. In addition, Germans began to become interested in using horse manure as fuel. You have to admit, this picture would have been paradoxical for a respectable and modern Germany just five years ago, when everyone believed in a future without problems and worries. However, what emerges instead is a picture more typical of the 19th century and there is always the risk that this “archaization” will affect more than just the heating or energy sector.

Despite all these disasters, the patient and disciplined Germans, who have been taught for 70 years that full submission to their state would ensure their guaranteed prosperity, are in no hurry to move into action to stimulate the government to find ways to solve this challenging situation. The exceptions are the German states of the former GDR, where social training has been going on for only 30 years, and where, due to general lower incomes, any upheavals are much more keenly felt. Protests against energy and economic “suicide” took place in Leipzig, Berlin, and Zwickau. In various cities, tens of thousands of people marched under the slogan “Heating, bread, and peace – protest instead of freezing”. Since the main organizers of the protests were the opposition Alternative for Germany and the organizations Freie Sachsen and Volksstimme Bürgerbündnis Zwickau, the government decided to discredit these actions in its own way, presenting that the rallies were not attended by citizens, but by far-right radicals and “fascists”. They will also probably try to attribute the “sabotage” that took place at Deutsche Bahn not so long ago to abstract radicals.

In West Germany, such explanations will probably succeed for a while since the power of brainwashing is too great. But here, too, confusion and tension gradually set in. So far it is not reflected in the streets, but in sociological surveys. According to the Infratest dimap poll for the ARD television channel, four out of five Germans (80%) evaluated the economic situation negatively, 47% of them as “less than good” and 33% as “bad”. These values are almost double the ones of the survey conducted under the previous government in 2021, and reached a record high value since 2009 when Infratest dimap began to assess the dissatisfaction of citizens one year after the start of a global crisis. That year, the dissatisfaction rate was just over 70%. The new survey shows that the situation in Germany is worrying for 85% of citizens, 34% higher than in the last similar survey in 2020. Only 11% have confidence in the future, a drop of 33% from the last survey and a record low since measurements began in 1997. The majority of those surveyed (53%) believe that the economic situation in Germany will be worse in a year’s time than it is today. One third (32%) expect it to be about the same, and only 12% are of the opinion that the economic situation will improve in a year.

Of the actual mass protest actions, also indirect ones can be noted: German private households and small companies increased indeed their gas consumption in the fall, despite calls by the authorities to reduce demand. However, the population’s problems caused by rising prices are taking quite tangible forms and the first to suffer from them were already the most unprotected and vulnerable: the pensioners. Once, along with Scandinavians, German elderly people were considered to be very well off and even rich. Nevertheless, the situation is tragically changing. It was the members of the older generation who were the first to complain about excessive electricity prices, which they simply could not afford. Moreover, the representatives of the country’s supporting middle class, who have never had any problems with money, also feel the difficulties. An expert of the luxury services market has reported that the once perfectly solvent middle class can now barely afford even the modest pleasures of going out to eat and getting new phones, to say nothing of the fact that expensive brands have become almost unaffordable for the overwhelming majority. The last chance for such luxury business is the upper class, which, according to the expert, “enjoys a stable position” and will continue to do so during the crisis. But the hopes that demand will recover within the next six months, as it did after the pandemic, are most likely not imaginable.

Even government agencies, which have always been stingy with populism, are not expressing optimism. The federal government expects a recession next year and a continued high rate of inflation. In 2023, the authorities expect inflation to remain at 7%, despite measures to reduce gas prices. Knowing Scholz’s “caution” in his statements, we can safely multiply this number by half. The situation will be no better with economic growth. This year, the government expects economic growth of only 1.4% and in 2023, the gross domestic product is expected to decrease by 0.4%, and that is in the most optimistic case. Germans used to laugh at the economic difficulties of Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece, but in the near future Germans may find themselves in a similar situation. Frugality, healthy pessimism, and saving for a rainy day: this is the new German credo. If it may last for decades before a real revolution takes place in Germany, the psychological upheaval in consumerist thinking is right before our eyes.

Top site ,.. amazaing post ! Just keep the work on !