Elections in Moldova as an example of the end of the “era of liberal democracies”

Moldova, after Georgia, became another country where the confrontation of political blocs within the framework of the “Cold War 2.0” put freedom and democracy on the “altar of expediency”. Read about how Western countries helped Sandu to keep his post against the will of the voters in our article.

History of the conflict

Presidential elections in Moldova were held in two rounds on October 20 and November 3. They were positioned by experts as a new episode of the traditional confrontation between Russia and the EU, Romania and the USA for influence on the poorest state in Europe.

Against the background of the war in Ukraine, control over Moldova has become extremely important for each of the parties. The coincidence of the presidential election with the referendum on the country’s accession to the European Union has spiced up the next clash. Vladimir Putin’s agents of influence and the incumbent president, Maia Sandu, linked to Romanian, European and American lobbyists, wanted to present the referendum as an event that would determine the fate of the country. For Russia, it is a tragic moment that could sever historical fraternal ties with Moscow, which is unacceptable. For Moldova, it is an opportunity for the country to join the EU, which will open up unprecedented opportunities for economic growth and prosperity.

But any outcome of the elections will only slightly adjust the status quo. Russia will still retain its influence on Chisinau through Transnistria. Romania will continue to hoodwink Moldovans with “European prospects” and opportunities for merging into a single country, which will remain pipe dreams due to their disadvantage for Brussels and Bucharest for economic reasons.

Such hopelessness without real choice has been accompanying Moldova for many years and the citizens of the country and politicians are very tired of it. But despite the common sense of the problems, it was not so easy to get out of the vicious circle. After all, until the mid-2010s, there were no other alternatives in the successive succession of pro-Russian and pro-European presidents, behind whose backs stood the puppeteers known to everyone.

Photo by Fabian Sommer/ dpa

In this October’s presidential election in Moldova, the main contenders are the pro-European candidate, incumbent head of state Maia Sandu, and her pro-Russian rival, former Prosecutor General Alexandr Stoianoglo. The latter has in a sense become a unified opposition candidate after Sandu pressured influential politicians such as Ilan Shor and Igor Dodon to drop out. Sandu deliberately split her opponents before the elections to weaken their chances.

Photo by Libertatea.ro

Is this simplistic explanation of their scheming correct? Ten years ago, the answer would have been “unequivocally yes”, but a lot has changed in the meantime. And the issue is the political understanding of what “Europe” is and what kind of politician can be called “pro-European”. During this time, the vision of Europe of Emmanuel Macron, Olaf Scholz and Ursula von der Leyen has diverged greatly from that of Giorgia Meloni, Viktor Orbán and Marine Le Pen. Each of these groups, in its own way, claims a “European brand”. In this sense, Moldova is just a projection of mental conflicts with its own unique specificity. In addition, Moldova was seen differently in the United States, where Republicans and Trumpists did not seek to support Sanda, who played in favor of an establishment hostile to them. However, the role of Moscow as the main enemy remained unchanged for Europeans and Americans.

In this dualism, Maia Sandu was a typical liberal populist who promises to solve all problems with the magical “power of the EU”, which gives birth to any good practically from the Holy Spirit. This rhetoric is familiar to almost every Italian and most have already acquired immunity from it, perceiving any generosity of bureaucrats from Brussels with caution. What about the Moldovans? For a long time they believed in the possibility of EU integration and even unification with Romania, but the political adherents of such a path constantly deceived them.

Sandu was no exception, and she even did not allow the country’s residents to assess all the disadvantages and nuances that await them on their way to EU membership. Everything was much simpler: citizens simply received a de facto refusal to realize their aspirations, against the background of which the referendum on the country’s accession to the EU, which was held together with the elections, looks like a real mockery. Because of this, many Moldovan citizens, who are liberal and even anti-Russian, have time and again chosen a worse, but more reliable way of coexistence with Moscow. And this is a big risk for Sandu’s patrons, so they chose the more reliable way, albeit illegitimate.

The first round upset the liberals

Already at the very beginning, Sandu chose a rational tactic with an emphasis on political technologies. Along with eliminating her main opponents, she limited foreign voting in Russia, where the electorate was clearly not in her favor. She also incentivized voting in the EU, especially Italy, where migrants from Moldova would clearly support her.

Such steps should have balanced the electorate when voting. According to the first-round polls, Sandu would not get more than 40% in the most optimistic situation, but the referendum promised an outcome of 60% “for” EU accession. This gave hope that more than 50% of voters would immediately support her candidacy, despite skepticism. Such a situation could have been protected in a situation where victory would have been achieved with the help of the resources of the state apparatus.

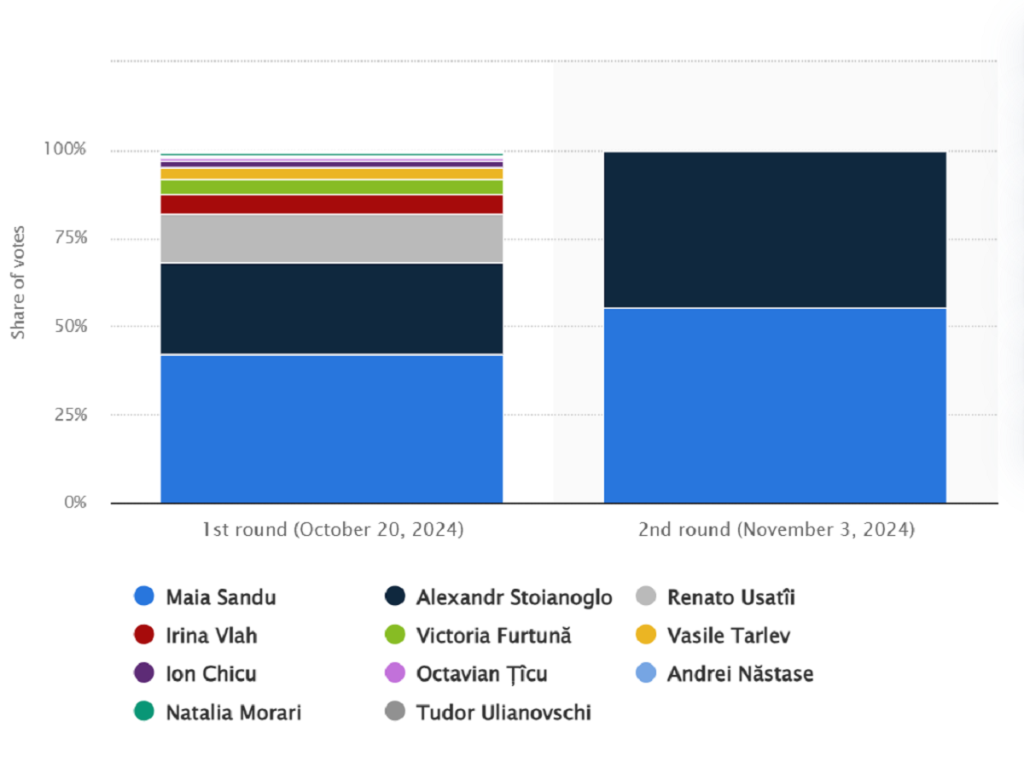

However, it was not possible to achieve such harmony, and on November 3, Moldova faced a second round of elections, as none of the candidates received a majority of votes. Sandu garnered 42.45% and Stoianoglo 25.98%. It is indicative that Sandu secured her lead mainly through foreign votes, receiving 70.71% from abroad. Sandu failed to gain a majority in Chisinau, receiving 48.32%. Moreover, the liberal electorate did not help her in Balti, the second largest city in the republic, where Stoianoglo won with 34.14% against Sandu’s 21.11%.

As in 2019, the results in traditionally pro-Russian regions were a failure for Sandu. In the Gagauz autonomy, she came fifth with 2.26% of the vote against Stoianoglo’s 48.67%. In Transnistria, Stoianoglo received 35.41%, while Sandu received 25.21%.

Already at the start of the counting it became clear that there was no question of winning the first round, and the referendum on EU accession, which was supposed to be the catalyst for Sandu’s triumph, risked failure. Moreover, the referendum has become a burden she must carry regardless of her own successes, because it was an ironclad condition of her partners and sponsors in Brussels.

Almost all day long, opponents of EU membership had about 52-55% against 45-47% for its supporters. Only after receiving the results from abroad, which probably coincided with a slight “correction” of the results by the country’s Central Election Commission (CEC), the scales tipped in favor of Sandu’s position. 50.35% of voters voted in favor of the change in the country’s Constitution, while 49.65% of voters voted “against” it. This was a Pyrrhic victory that showed Moldova’s split. The problem was also the fact that the majority of Moldovans voted against joining the EU in the referendum, while in Gagauzia 94.84% preferred full sovereignty and orientation towards Russia.

Maia Sandu at one stage even wanted to cancel the results of the first round, citing “Russian interference”. But the need to “preserve” the results of the referendum put an end to this radical step, which would have further undermined the democratic nature of the elections, which is still of minimal importance to the EU and to Russia. And this made Sandu’s position almost critical.

There was a difference of 57,204 votes between the number of those who voted in Moldova’s presidential election and in the referendum. These were those who boycotted it at the call of the opposition. This probably helped the dubious victory of European integration, but hurt Sandu, because all these people would have voted against the incumbent in the second round with a 99% probability. For her, the European referendum had the sole purpose of mobilizing the nuclear electorate and ensuring her victory in the first round. For the sake of this, they hastily changed the electoral code, which prohibited combining the referendum. They also ignored the Venice Commission, which prohibits such changes less than a year before the elections.

But failure happened, showing the fallacy of the EU’s bet on Sandu. And if even 10% fewer Moldovans voted in favor of EU membership, the president’s anti-rating would have buried the referendum. But the lot was cast, and Sandu’s punishment for her miscalculations in the first round from her “partners” in the EU and the USA could only be personal and completely negated logically her defeat on November 03.

The second round reveals the cards

Before the second round, it was of great importance who Renato Usatîi, who came in third place with 13.79%, would vote for. But he did not take a clear position, although his electorate was negative towards Sandu. At the same time, almost all the other candidates, with a total of 13%, explicitly stated that they sympathized with Stoianoglo. With strict analytics and sociology, the result of the second round seemed absolutely unambiguous, but Sandu had a huge administrative resource and enormous support from the West on his side.

Prt scr Statista.com

The voting in the second round started with some oddities that led to a repetition of the scenario of the referendum on EU accession. First, Sandu accused two major observation missions of “wrong” observation – the OSCE mission and the Moldovan association Promo-Lex. They were previously loyal to Sandu, but became toxic for her as they noted many irregularities in the organization of the first round of elections and the referendum of the ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS).

Then, due to imaginary mines, the bridges over the Dniester were blocked, through which voters from Transnistria disloyal to the president could arrive to vote; many of them never made it to the polling stations. Finally, for almost the entire day there were no results or even exit polls. The first results were summarized only around 23:00, when, after counting about 76% of ballots, Stoianoglo was leading with 52.07% against Sandu’s 47.93%. And such a gap was already easily covered by the votes of Moldovans from Europe and the USA, which made the situation for the president extremely comfortable.

In the end, there was no miracle, Sandu started to advance very quickly. By midnight, after processing 100% of the ballots, she had already surpassed Stoianoglo with 55.33% against her opponent’s 44.67%. At the same time, despite many pre-election reports about the threat of pro-Russian protests, Stoianoglo urged people not to take to the streets, recognizing the results as legitimate.

As in the first round, there were many sociological oddities and indicators that made the victory flawed in terms of political legitimacy, although Sandu’s EU allies and the European media cheered. First, there was the usual abnormally high number of overseas votes for Sandu, where she won by a margin of nearly 80% to her opponent’s 20%, even though voting opportunities were extremely limited at polling stations in Russia. Stoianoglo won almost 51% of the vote in Moldova itself, almost 80% of the vote in Transnistria, over 90% in Gagauzia, and even beat Sandu in her hometown.

This creates many problems for Sandu, as the election results were not a triumph for her, but a harbinger of big problems for her next year, when the parliamentary elections will be held. After all, she became president solely thanks to the votes of the European diaspora. And if we take the results of the elections in Moldova itself, the opposition socialist Stoianoglo, who relies not only on Russia, but also on the European right-wingers close to Donald Trump, won there. She should not expect a quiet rule.

The situation around the elections and referendum in Moldova, as well as in Georgia, testifies to the crisis of democratic procedures in the countries of Europe and the entire West. More importantly, in countries that relied on popular democracy as their ideology. “Cold War 2.0” even democratic countries dictate behavior where preservation of power is more important than “electoral formalities”. And there is a risk that such “formalities” will be resorted to less and less often, and elections will be remembered later as a standard of democratic approach, although they are not.

From the periphery of the EU and the U.S., such an approach can very quickly spread to the “metropolis” itself. Similar to the last U.S. presidential election, the degradation of democratic institutions will be presented as their defense, and the experience of Russia and even China will be adopted. That is why one should not take everything that is happening as a given, which happens in “backward” countries or is done in the name of containing Moscow.

After all, when wrong steps are taken in the name of a good goal, they themselves eventually become a distorted goal. And the rejection of democracy and real legitimacy will definitely become a mental defeat for Western civilization, which for the sake of “expediency” will push it into a new era of darkness and hopelessness and lead to defeat in the “Cold War 2.0”.