“Trade wars” are not off the agenda, even though their full version has been postponed

Trump’s “tariff shock” strategy has triggered a chain reaction – from panic in markets to the reformatting of global alliances. While China is consolidating its position in Europe and the US is trying to maintain influence through deals with Britain and Italy, key production chains are already being irreversibly altered. This crisis goes far beyond economics, reshaping the entire system of international relations.

“Tariff rollback”: how markets and businesses have held back Trump

Trump startled the world with his determination to impose huge tariffs against most of the world’s countries. But a week later, the presidential administration partially canceled them because of panic in the markets and the risk of recession in the United States. The White House said that it was only a “test” of other nations’ reactions, and now within three months there will be talks on possible duty reductions.

The White House quickly realized that it will not be able to wage a trade war with the whole world and the main blow is now directed at China. Meanwhile, the markets reacted with growth to the softening of Trump’s trade policy amid public pressure. By the way, a roughly similar situation may develop on other fronts, in the context of negotiations with Iran. And Trump’s governors themselves already feel that they are playing with fire. And if a recession starts, the White House could be running out of popularly approved reforms, which benefits no one but the enemies of the Trumpists.

Soon the first details of what was going on in the Trump administration during the week-long trade war with the rest of the world emerged. It turned out that American businesses had pulled all their lobbying levers in an attempt to get Trump to reverse the imposed tariffs. Watching the markets react negatively – especially in the US debt market, where government bond rates rose while demand fell – Trump was forced to reconsider his harsh tariff policy. The prospect of even a technical recession threatening his ratings has forced the president to push back tariff radicals like Peter Navarro and increase the apparatus weight of Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. He is a proponent of “escalation to de-escalate”, that is, scare tactics for the sake of further favorable compromise.

“Escalation for de-escalation” has already de facto happened in relations with Panama, when first the White House threatened to forcefully establish control over the canal, and then simply made a deal on favorable conditions for the passage of US Navy ships through the canal. And now it cannot be ruled out that in the end we will see a similar outcome of the chaotic trade war.

All the more so as the White House kept lowering the degree of trade wars. Soon all smartphones and computers imported into the US were removed from the scope of duties, while chips from Taiwan were not subject to tariffs at all. It is indicative that the majority of computer electronics comes to America from China, which has remained the main “tariff enemy”. For example, 86% of game consoles, 79% of monitors, 73% of smartphones, 70% of lithium-ion batteries and 66% of laptops are imported from China. And Trump’s tariffs against China would lead to a shortage in the computer electronics market, hence the urgent backlash.

It was still a very worrying sign for US companies, though. Apple is ramping up iPhone production in India (15% of current volume, plans 25% by 2027) and Vietnam in an effort to reduce dependence on the PRC. With New Delhi, it is certain that the White House will soon try to sign a trade agreement to reduce duties, and negotiations are underway with Japan, South Korea and Vietnam. The latter also produces a lot of Apple equipment, and the first round of negotiations with Taiwan was held with the same motivations, when local chip production was immediately removed from the tariffs. It is expensive and difficult to move any significant production to the US, even if we are talking about the chip assembly of the same iPhones. The tariffs will not help, and American business will try to continue moving to India and Vietnam if they can reach a quick agreement with them. But even in such a situation, the US will still be dependent on supplies from China for many years to come.

Britain and Italy at the center of a trade standoff

The White House is stepping up trade talks with its partners, and now Britain is in the lead. London enjoys a trade surplus with the US and is seeking a “model” agreement that could set an example for the EU. But the UK has its own challenges, including its dependence on Chinese investment in eco-projects important to the green transition. In addition, China is negotiating with the Europeans to wage a joint standoff with the US. China continues to cut trade with the US and is abandoning Boeing airplanes. This is a blow to America that also has an important symbolic character for Trump, because he is making a big effort to save Boeing from collapse. The corporation has even been awarded a contract to build new F-47 fighter jets, but Boeing is still doing poorly in the civil aviation market. So it is quite possible to reach an agreement with Great Britain, but it will not solve the key problems of the USA. Therefore, the White House is more important to negotiate with India, Vietnam, Japan and other Asian countries. In the meantime, the White House will try to fight China and the European Union at the same time, if it has enough strength to confront two fronts, which may eventually merge into one.

In Trump’s trade wars, Italy has suddenly come to the forefront. The country’s prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, is seeking to lead US-EU negotiations by leveraging ties to Trump’s team. Italy, Europe’s third-largest exporter to the US (agro-products, wines, pharmaceuticals), is seeking a compromise – and so actively that European negotiators have even switched to disposable phones to protect against leaks. In fact, the White House demands that the EU cut trade with China in every possible way, but the Europeans are not ready to do that because of the enormous trade turnover with China of $830 billion. On the contrary, Chinese companies are now trying to occupy European markets, taking advantage of the situation of uncertainty, so the negotiations will obviously go hard.

The situation is complicated by the Italian Aponte family, which owns MSC and is trying to acquire 40 port terminals, including former assets of the Anglo-Chinese conglomerate Hutchison. True, China, amid a trade war with Trump, has already blocked the Hutchison sale. And China’s relations with Italy have not been the best at least since Meloni withdrew from the One Belt, One Road Initiative. So Meloni will have a difficult task: to find a balance between American demands and European interests in the midst of a global trade standoff.

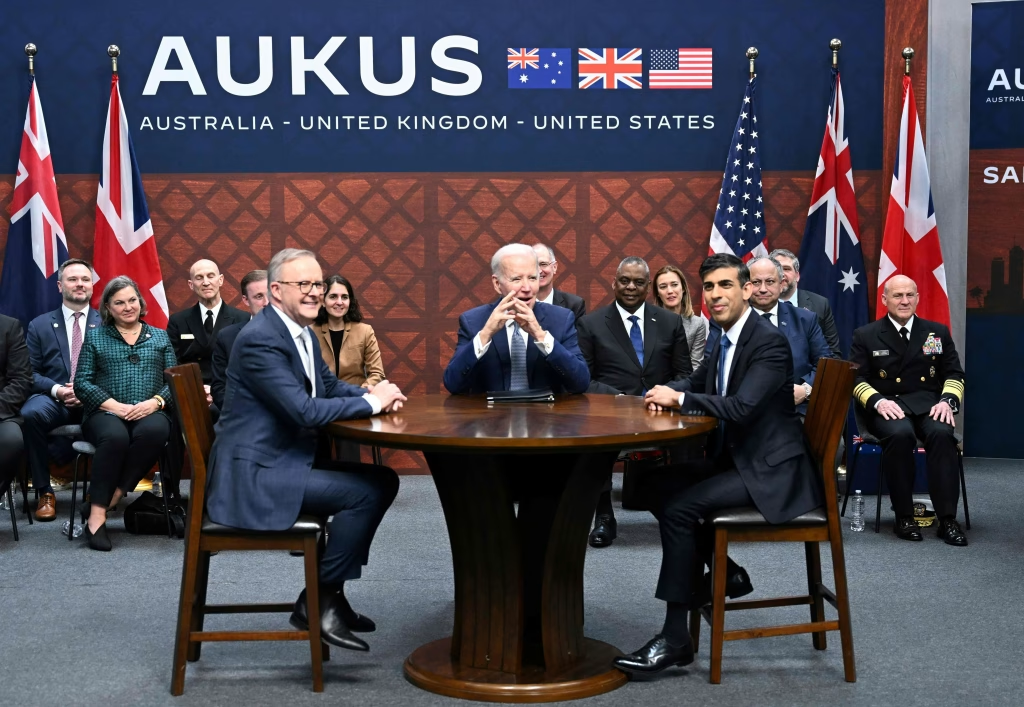

Trump’s tariffs call into question the future of AUKUS

An unlikely casualty of Trump’s trade wars could be the AUKUS treaty, which is already falling on hard times. Under the 2021 agreement, Australia was already supposed to start receiving old US subs that the Pentagon is scrapping, but difficulties have arisen. The deadlines, as usual, are being severely stretched and are being affected by long delays in the production of new subs in the US. Now it takes the Pentagon 9 years to build one submarine, although recently they were assembled in 6 years. And here the shortage of raw materials coming to the US from other countries can also manifest itself. In particular, up to one third of all steel and aluminum used in American shipbuilding are imported to the US.from Canada and Great Britain, and now these supplies are subject to duties of 10-25%, which even in case of their “freezing” the effect has already been realized.

There is also a shortage of rare earth metals, previously coming from China, because the construction of one submarine Virginia-class need up to four tons of such resources. Now Canberra is promised to receive the first US submarines no earlier than 2033, and the terms for the creation of new submarines of the AUKUS project are shifted somewhere to the 2040s. Moreover, Trump’s team has started demanding that the Australians pay more for the subs, otherwise the Americans threaten to withdraw from the project and leave Canberra with nothing. In addition, Australia has also been hit by tariffs, and now the Labor Party in power there promises to reduce dependence on the US and work more actively with other markets.

Against the backdrop of these centrifugal processes, the future of AUKUS becomes quite vague, and the project may well collapse during Trump’s current term. And this is not the only consequence of the “tariff wars”, which, as it mistakenly seems, are almost over. After all, the US fight with China is a deadly battle that doesn’t depend on the mood in bond markets or Trump’s reaction to Wall Street’s discontent. And the mental standoff between Brussels and Washington is not dependent on tariffs and cannot be undone. The world will never be the same again and trade wars will not be off the agenda one way or the other.