Polish nationalism: the wealth and misfortune of the Polish people. Part 2

We have talked about the importance of nationalism in Polish society before, and ended with the fact that Polish nationalism relies on political movements and soccer fans. The backbone of many nationalist groups and an independent force in their own right are precisely Polish soccer fans, who have become a huge force in the last 20 years. If you ask any European fan to name the most violent soccer fans on the continent, and in the top three he will definitely include Polish hooligans. Similarly, Poland is considered by most soccer fans to be one of the most dangerous countries, maximally unsuitable for visits with their team. It started back at the turn of the 90s and 2000s. The riots during a game in Warsaw in 1999 gave rise to years of debate over the behavior of Polish hooligans who used knives during a brawl at Saxon Garden (Ogród Saski). After that, there were dozens of similar incidents from Polish fans. While most of the hooligan fights took place without lethal weapons, the Poles were not afraid to kill their opponents.

In addition, Poland is also characterized by another aspect of soccer fans’ behavior that is of growing concern to the European authorities: racism. There is no doubt that, along with neo-fascism, it is the most widespread in the stands of Polish stadiums, so much so that some banners put up by local hooligans openly display Nazi symbols. This is mainly due to the activities of the fascist party “National Revival of Poland”. Its representatives enjoyed great success in the stands of stadiums, when in the not too distant past they recruited hooligans into the so-called “national revolutionary cells”, which led to an extreme hardening of the entire soccer subculture, which, unlike other countries in Europe, where there are groups, albeit no less aggressive, but left-wing radicals, is exclusively nationalist and right-wing. There is documented evidence of how some soccer players put pressure on the management of their teams, preventing them from signing black players. When the first black soccer player, Emmanuel Olisadebe, joined the Polish national team, the move was met with strong condemnation in some Polish media. The Polish authorities and the national media shield their fans from the EU’s attempts to systematically combat their nationalism, which unites the authorities and soccer radicals. Most Polish soccer clubs have nationalist ultras. The first fan groups appeared at the soccer clubs Legia (Wrocław) and LKS (Łódź) in the early 1970s. Over the next 20 years, similar organizations formed around other Polish teams, including Polonia (Bytom), Wisła (Kraków), Lechia (Gdańsk), Śląsk (Wrocław), Ruch (Chorzów) and Pogoń (Szczecin). The fans participate in the organization of the Nationalist March, which takes place in Warsaw on the occasion of Polish Independence Day on November 11 every year and attracts up to 50,000 participants. In recent years, scuffles between participants and police or other fans have been a regular occurrence during the Independence March. During the march in 2013, radicals set fire to a guard booth at the Russian Embassy, threw firecrackers at the diplomatic compound, and damaged several diplomats’ cars. The only participant of these events who was brought to trial was acquitted.

Paradoxically, in the 16th-17th centuries Poland was one of the centers of the Reformation and many Poles, especially the nobility, actively embraced Calvinism or Lutheranism. As a result, the Papacy managed to keep the country in the bosom of the Universal Church and it was a happy occasion for the Poles. After the last partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the depressed and confused Polish society began to gather around the Church, which became the most important center for the preservation of the Polish nation, and thus an integral institution of Polish nationalism. The Catholic Church performed essential functions, from propaganda of true “polandness” to raising funds to support numerous small and large Polish uprisings, both against Russia and against Austria and Prussia. It also played a major role in the re-establishment of Polish statehood in 1818.

The Catholic Church played a very important role during the period of communist rule in Poland, especially in the 1980s. On the one hand, it sided with the citizens, and on the other hand, it acted as a mediator in establishing a dialog between the government and the opposition. Church centers became centers of exchange of ideas and independent culture. The most important indicator of the influence of the Polish Catholic Church was the election of a Pole Karol Józef Wojtyla as Pope John Paul II in 1978. In democratic Poland, the church entered the 1990s with an incredible capital of merit, so its role today is historically defined. “Attention should be paid to the cultural aspect of the meaning of religion in Poland, embodied in identity, customs, regardless of the degree of faith practiced. In Poland, religion is a matter of connection not only with faith but also with culture. It shapes the Polish social identity of Poles” – said Sinowiec, one of the Polish experts in the field of culture and religion. From this stems the role of the church in politics. And because of its natural conservatism, the Catholic Church gravitates towards nationalist ideas and political forces. In the early 1990s, after the fall of communism, the Church abandoned its role as mediator between the government and the opposition and slowly began to increase its influence in the state. This became particularly noticeable during the period of the “Law and Justice” government, when in practice one can speak of the party making a pact with the Church hierarchs and, importantly, with the Catholic media. In recent years, the Church has become even more involved in politics. Its influence can be seen in social policy, family policy, moral discourse, and the Church institution is now seen as part of a power structure that is nationalist. The church also feeds nationalist organizations such as Ordo Juris, a far-right organization that, among other things, lobbies for the introduction of a law in Poland completely banning abortion.

From 1918 until the Nazi occupation of the country in 1939, Poland was ruled by nationalists of varying radical degrees: from the far-right, strong-willed Marshal Józef Piłsudski, who became famous for his anti-Semitism and anti-communism, to the inarticulate Ignacy Mościcki, who led Poland to political and military disaster. Ironically, political nationalism in Poland experienced a definite crisis in the 1990s. In 1990, Lech Wałęsa, who could be classified as the liberal wing of the Polish opposition, which fought against the communists and the influence of the USSR, became president. Against the background of the “shock therapy” that affected all post-Soviet countries of Eastern Europe, a moderate socialist, Aleksander Kwasniewski, who served two terms as president from 1995 to 2005, came to power.

In mid-2001, as a response to the vacuum on the nationalist flank, the Law and Justice party appeared on the Polish political scene. It was founded by the Kaczynski brothers, who had built their political careers back in the days of Solidarity, a Polish association of independent labor unions created in the midst of massive anti-communist strikes that began in 1980. Law and Justice first came to power in 2005, but lost it two years later due to a weak parliamentary coalition and accelerated parliamentary elections. For the next two parliamentary terms, the party unsuccessfully tried to regain its leading position. Jaroslaw Kaczyński was also the party’s candidate in the 2010 presidential election, after his brother, then-President Lech Kaczyński, was killed in a plane crash. Despite defeat in the presidential and parliamentary elections, the party did not abandon its attempts to lead the parliament, which succeeded five years later. In 2015, Andrzej Duda, then a member of the party, takes over as president (he was also a Law and Justice MEP in 2014-2015), and the party finally leads in the parliamentary elections. The number of mandates allowed the party to actually govern on its own, without having to form a coalition. Since 2015, where the representatives of Right and Justice were the president, the prime minister of the Sejm, a nationalist authoritarian model has been formed in Poland, in which the nominal deputy speaker of the government and the head of the Law and Justice, Jaroslaw Kaczyński, became the de facto head of state.

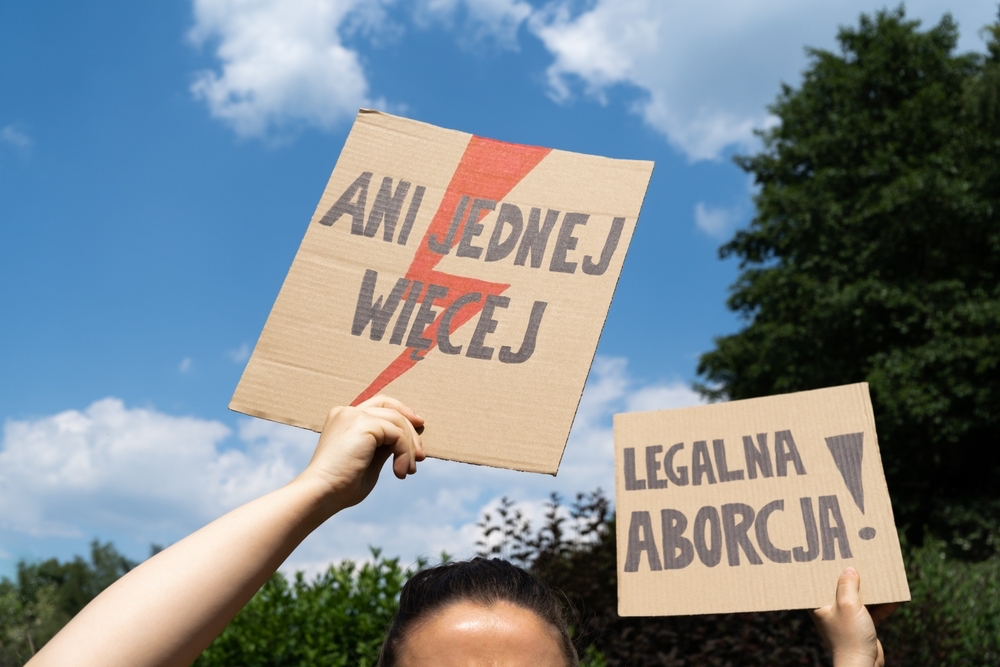

He and his party concentrated all power in one hand for seven years, destroying democratic institutions in the process. The government set dangerous precedents for the non-implementation or circumvention of established laws, including the Constitution. Dismantling the Polish judiciary, prosecutor’s office, government administration, security forces, and attempting to stop the development of civil society. In foreign policy, he tried to make Poland a regional leader by interfering in the internal politics of the Baltic States, Ukraine, Belarus, and even Slovakia and Hungary. He constantly criticized EU structures and clashed with Brussels, creating the Visegrad Group that promoted U.S. interests in Europe. In domestic politics, he pursued a nationalist populist policy based on Russophobic speech, increasing the role of the Catholic religion in the country, restricting migration and banning abortion. This fit perfectly into the notion of Polish nationalism and met with understanding, approval and enthusiasm among Poles. The liberal stance of Law and Justice, however, has rather shaky grounds. Andrzej Duda won only the second round in 2020 with a modest 51.03%, defeating the candidate of the liberal and pro-European Civic Platform, Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski. Polish society is ultra-conservative by European standards, but even in this environment, cosmopolitan ideals are growing steadily among the younger generation of Poles. Every next election threatens Kaczynski with the loss of his monopoly on power. Especially since the European Union, with which Kaczyński has been waging a kind of “cold war” for a long time, both mentally and organizationally, is interested in removing Right and Justice from power and is ready to give any alternative force all possible support. And, therefore, the fate of political Polish nationalism hangs in the balance. Whatever happens, however, nationalism will be both the hope and the pain of the Polish people for a very long time to come. And probably, in 10-15 years, Europe will be completely different, and Poland will occupy a completely different place in it.